The J.: Hundreds descend on Sacramento to lobby for Jewish interests

BY GABE STUTMAN | MAY 19, 2022

Willie Armstrong, the chief of staff to state Assemblymember Chris Holden, looked rushed. The former Air Force service member, wearing a dark suit and an American flag pinned to his lapel, had only 10 or 15 minutes to spare before he needed to get back to his office during a busy period in the legislative calendar.

With his fingers clasped in front of him, Armstrong nevertheless listened politely as a half-dozen Jewish lobbyists — unpaid ones, gathered in the common area of a Sacramento office building — began to nudge Armstrong to nudge his boss, the powerful chair of the Assembly’s Appropriations Committee, to support seven Jewish priority legislative measures.

Armstrong made eye contact and asked questions, particularly about surveying the state of Holocaust education. Holden, of Pasadena, already supported some of the measures being discussed; others Armstrong said he would look into. The chief of staff remained standing throughout the brief meeting.

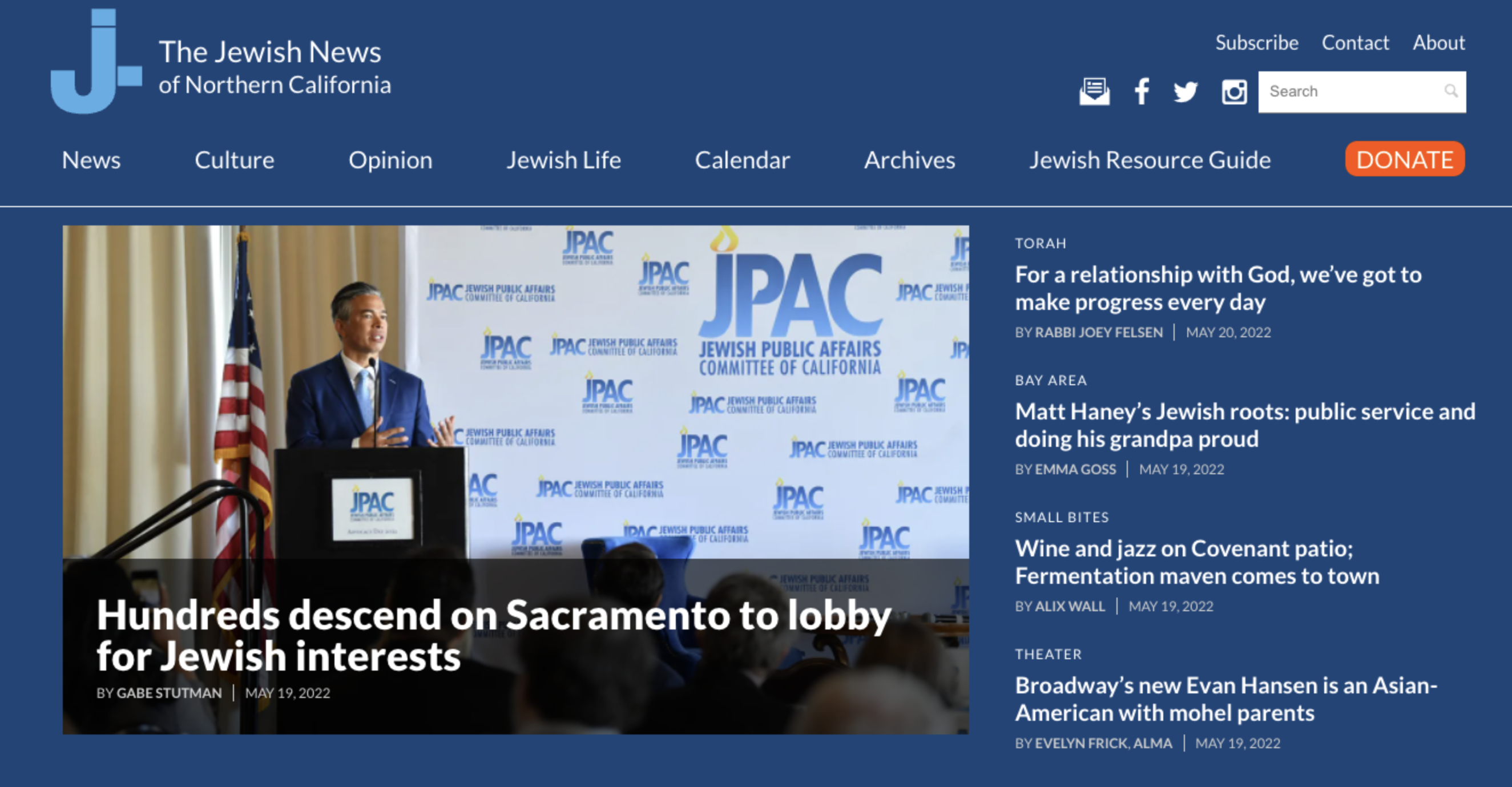

It was a scene replicated in dozens of lawmakers’ offices last week, when the most influential Jewish advocacy network in California state politics — the Jewish Public Affairs Committee, or JPAC — held its annual keynote convention, in person, for the first time in three years.

Over two days, hundreds of politically minded Jews convened and then reconvened for speeches, award ceremonies and policy discussions in the seventh-floor ballroom of Sacramento’s elegant Citizen Hotel. The event drew big names in California politics — Attorney General Rob Bonta and Lt. Gov. Eleni Kounalakis among them — and in the worlds of Jewish philanthropy, lawmaking and business. There was a lot of schmoozing and networking. The lines for food were long.

The culmination of the policy conference, though, is “Advocacy Day,” which happens on the second day. JPAC describes it as an “advocacy experience” — sort of like a Major League Baseball fantasy camp for the politically minded.

JPAC was established 50 years ago with the goal of uniting Jewish community interests under one umbrella group in the state capital. In 2020 it canceled its conference because of the pandemic, and last year the event was held virtually.

The organization defines itself in many ways — as “the voice of California’s Jewish community”; as the “largest single-state coalition” of Jewish community organizations in the country; as “California’s organized Jewish community convener.”

What it really is is an advocacy (or lobbying) organization that purports to represent California’s approximately 1.2 million Jews. A daunting task, considering the range of political opinions held by Jewish Californians. Nevertheless, with some nimble political maneuvering, JPAC aims to build consensus around a slate of bills each year.

“We recognize the value of coming together under one voice,” executive director David Bocarsly said in a recent interview. “It allows us to all gain.”

Bocarsly, 31, a Conservative Jew who wears a kippah, was hired away from the California Legislative Jewish Caucus late last year. He now quarterbacks the whole thing along with the JPAC board and with help from Cliff Berg, a registered lobbyist in Sacramento.

To form its agenda, JPAC works with 30 partner organizations (Federations, Jewish Community Relations Councils, the Anti-Defamation League and other nonprofits), whose leaders sit on the JPAC board.

Some of the bills it chooses to back affect the Jewish community directly — such as funding for the Nonprofit Security Grant Program, which bolsters synagogue security, or state funds to support Holocaust centers in San Francisco and L.A. Others are not so direct — funding for food benefits for undocumented immigrants and a slate of bills that tackle poverty and health care.

JPAC has also advocated for gun control measures, affordable housing and bills that combat human trafficking.

“I like to say the work falls under two pillars, the first being support for core Jewish community needs. And the second being support for core Jewish community values,” Bocarsly said.

“And we’re careful not to touch on issues that might be too polarizing to some of our community organizations,” he added.

This year JPAC selected 38 bills and budget priorities to support. The full list can be viewed here.

A 501(c)4 nonpartisan nonprofit, JPAC raises money primarily through membership dues paid by its partner organizations. It also charges between $100 and $150 for tickets to Advocacy Day (plus add-ons for special VIP opportunities, such as dinner with the California Legislative Jewish Caucus). Bocarsly said the fees help fund the event but don’t fully cover its costs.

The convention saw Bonta and Kounalakis give keynote addresses on the importance of combating antisemitism, and lawmaker-led panels including “combating hate through coalition-building” and “serving immigrants, refugees, and asylum-seekers.”

The conference this year saw about 200 attendees, many of them affiliated with JPAC partner organizations like Jewish Family and Children’s Services and Jewish Federations, and others not affiliated directly with large nonprofits. The ADL brought one of the event’s largest contingents.

On Advocacy Day, JPAC splits all of the attendees into groups of about a half-dozen people. Each group is given a list of legislative priorities (this year it was five bills and two budget requests) that are among JPAC’s top asks. After a brief prep session, the groups fan out to the surrounding Capitol office buildings to take meetings with lawmakers and their staff.

JPAC provides instructions, spelling out the dos and don’ts of political lobbying: Do “be brief and to the point.” Do “read the legislator’s body language.” Do not “belabor your concerns,” and do not “mention fundraising or money.”

The goal is to talk to as many legislative offices as possible. This year, JPAC advocacy groups spoke with 88 of the 120 total.

J. tagged along with one of the advocacy groups, an effort that began with a strategy session over coffee and tea in the ballroom. Our group, or “team,” ranged in age, religious observance and experience with political advocacy.

Each person picked an issue from JPAC’s list they would take the lead on. Renee, a man with a closely cropped gray beard and cloth cap, had parents who survived the Holocaust and many relatives who did not. He picked a Senate bill targeting Holocaust education. Eli, a slight, retired physician who wore a matching pin and tie depicting the Israeli and American flags flying together, would advocate for measures to increase food and health benefits for undocumented immigrants.

Josh, a Chinese-born, millennial Jew and the only kippah-wearing member of the group, would vouch for an increase in Nonprofit Security Grant Funding. Fellow millennial Jeff, a public policy professional with JFCS in San Francisco, would talk about the hate symbols bill introduced by East Bay Assemblymember Rebecca Bauer-Kahan. Cathy, team leader and coach wearing a polka dot blouse, made sure everyone was on the same page and spoke across a number of different topics. Donna, the wife of the retired physician, said she preferred not to speak during the meetings but offered her two cents every now and then.

After a fajita lunch, we walked a few blocks to a temporary legislative office building (the Capitol complex is under construction). The building was thronged with activity, not only JPAC advocates but others, including medical industry lobbyists wearing white coats.

Our first stop was at Holden’s office where we met with the chief of staff.

We had seven topics to hit and only minutes for each because of Armstrong’s time constraints. After some hurried introductions and the exchange of business cards, Renee spoke about SB 693, which would create a large-scale study to assess Holocaust and genocide education in California. He told of his parents’ escape from Nazi-occupied Europe to Shanghai. He said many of their relatives were murdered, and referenced research showing about two-thirds of millennials don’t know basic facts about the Holocaust, including that 6 million Jews were killed.

Armstrong’s demeanor began to soften. He couldn’t hear Renee well, so he moved closer, to the other side of the table where he’d been standing.

“If we do not learn from history, it will repeat,” Josh offered.

Armstrong listened attentively to Renee and to the rest of the presentations. He asked questions about funding, and where each bill was in the legislative process.

After 10 minutes or so, he told us his time was up, and he hustled back to his office.

The next stop was with, notably, a Republican lawmaker — the only one on our list. But since JPAC is a nonpartisan organization, nobody in our group used the word “Republican.” Instead we said the representative was with the “minority party.”

Thurston “Smitty” Smith is a former construction worker and cement company owner representing a vast district in southeastern California. Much of his district consists of the Mojave Desert, and its economy is powered by military bases.

“I’m just a guy who worked construction,” Smith joked.

He invited all of us into his small office. We wheeled in chairs, while Smith sat behind his desk next to a legislative aide.

On the wall was an American flag with the “DONT TREAD ON ME” symbol. Eli admired the flag and said he considered buying a similar one after 9/11.

Smith seemed to fully back some of our group’s bills. “I think we should have a whole semester on World War II history,” he said in support of the Holocaust education bill.

On some of the other bills, he was receptive but noncommittal.

The group asked Smith to support the budget measures to add food and health benefits for undocumented immigrants, and for seniors.

“I don’t see who benefits from people going hungry,” Eli said. “Particularly in the construction business. I don’t think you want someone who’s hungry fixing a roof.”

“What’s the request? Billions? Millions?” Smith said, adding that he does food deliveries for seniors as a volunteer.

He said if it were mere millions he could probably support it. But he also expressed reservations about the size of Gov. Gavin Newsom’s anticipated budget proposal. He said his staff had placed bets about how many tens of billions of dollars the Democrat would propose in spending.

Smith cracked jokes and showed the group some of the knickknacks in his office, like a trophy from coaching Little League baseball. He said he was one of the few lawmakers in Sacramento who owned a business, experience the group seemed to agree was sorely needed in the statehouse. He enthusiastically agreed to a group photo.

Our next stop was with a friend of JPAC — Assemblymember Marc Berman of Palo Alto, a member of the California Legislative Jewish Caucus. Berman hosted us in a conference room alongside a young staffer.

“I don’t think we need to do much lobbying with you!” Jeff said to laughter.

We had a free-flowing conversation not only about JPAC’s budget priorities, but about Bermans’ other legislative priorities.

Jeff, the millennial public policy director with JFCS, asked Berman which among JPAC’s bills he anticipated would see the strongest opposition. Berman said AB 587, introduced by Jesse Gabriel, the Jewish caucus chair. The measure would require social media companies to report to Sacramento on policies moderating hate speech, and on efforts to combat hate online. Groups like the ADL continue to advocate for more regulation of hate speech on the internet, including with this bill.

“I’m sure tech folks are opposed to it, and will be working hard against it,” Berman said, noting the bill would add a regulatory hurdle for social media companies, including those in his Silicon Valley district.

The conversation was casual; it was clear Berman already supported JPAC’s priorities. Describing his priorities for the year outside of JPAC bills, he named workforce development, particularly in the health care space, and programs to train teachers to teach computer science.

Our last stop was with San Francisco’s newly elected Assemblymember, Matt Haney. Haney wasn’t available, so we met with staffer Nate Allbee.

Haney had been sworn in only a week prior. It seemed the office was still being set up — Allbee didn’t even have his official email address yet.

We presented our bills. Josh talked about increasing funding to $80 million for the security grant program. He said funding was needed not only for physical features like gates and security doors, but for person-to-person trainings on how to de-escalate situations before they become violent.

Churches don’t need security. But synagogues do, Josh pointed out.

Allbee listened politely. Asked about Haney’s priorities, Allbee said confronting the fentanyl epidemic in San Francisco was at the top of the list. Eli, the physician, recommended an expert on the subject of addiction and withdrawal, and Allbee seemed to appreciate the referral.

Outside Haney’s office, team leader Cathy seemed pleased with everyone’s efforts. It was time to head back to the Bay Area, where most of us lived. We exchanged contact information and left.

To JPAC, the day appeared to be a major success. It was Bocarsly’s first year organizing the event. He called the convention “amongst the largest JPAC Advocacy Days in its history.”

“We had the most legislators participate in our conference than ever before, and we had the most meetings with legislative offices than ever before.”

Days after Advocacy Day, the governor released his revised May budget draft. JPAC sent an email to all of the attendees soon after.

“I’m blown away,” wrote Bocarsly. “As a result of our lobbying efforts, Governor Newsom included $93.2 million for JPAC priority items into his state budget proposal.”

JPAC didn’t get everything it wanted — Newsom’s budget included $50 million for the NPSG, not $80 million. But “The #CAJewishVoice is being heard,” Bocarsly wrote, adding an emoji of an arm, flexing its muscle.

To read the article on JWeekly, click here.

—

Gabe Stutman is the news editor of J. Follow him on Twitter @jnewsgabe.